This text is a compilation of quotes from primary and secondary sources, collected by Femke Dekker, Alice Wong and Simo Tse.

The reason we choose to approach writing this way is to reflect upon our processes of researching radio archives, or archives with radio content. Instead of inventing, radio relays and distributes; once a radio transmission enters the archive, it becomes raw materials again. And this is the attitude we want to encourage in which artistic researchers actively and autonomously engage with signs and information, and it is in our meandering that meanings are being put forward and re-examined.

Episodic, immediate and unselective towards its own audience, radio programmes accumulate in real time. The archives of radio content can be both institutional and private as long as the listeners have access to airwaves, the sounds and voices are up for grasp. The following quotes are meant to be read in sequence and are put together with linearity in mind. However, they have also been isolated from their original context and are now being read as connecting puzzle pieces. The fluency, rationality and sequentiality of these connections are up for reshuffling and rethinking from each one of you. It is like tuning out to different stations on an old radio, catching fragments of different voices across the ether. Again, we encourage you to expand on the vocabularies and grammar when it comes to sonic and radio research. The list is, by no means, and is impossible to be read as finite.

Disclaimers aside, we as artistic researchers should not be fooled by the seemingly authoritative tone of voice or the seamlessness of how information is put together. The cacophony of voices and noises in our surroundings requires us to listen care-fully: if the order of a sentence or even a single word changes, their meaning and context could alter completely.

MANUAL INDEX

1 HOW TO BEGIN?

AW There is no right way to begin. The way I start always stems from what I want to know. I begin by asking questions from scratch. I believe we often overestimate our own common sense. We think we know, but we actually don’t. And sometimes we assume we have no clue, but then, when we start writing or talking about it, we realise we aren’t as ignorant as we thought.

ST I remember, at the beginning of our project, we have also spent a long time framing and reframing the research questions. The difficult part often is to figure out what was unknown and what was to be make knowable.

FD I agree with the notion of no right or wrong way to begin. When it comes to sonic archives in particular, the sonic will lead you to reframe and rephrase continuously as if you are having a actual dialogue with a person.

• RECOGNISING AND RECKONING WITH THE NATURE OF ‘ARCHIVE’

• UNDERSTANDING RADIO AS MEDIUM

• WHAT/WHO TO LISTEN FOR?

2 HOW TO RESEARCH?

• WHAT ARE THE ROLES OF THE ARTIST-RESEARCHER-DESIGNER

IN ARCHIVAL RESEARCH?

• HOW DO WE PERCEIVE AND CONCEIVE INFORMATION FOUND IN AND

ALONGSIDE AN ARCHIVE?

• IT’S ALWAYS PERSONAL: MEMORIES VS. UNDERSTANDING

3 HOW TO TRANSLATE?

• KILL YOUR DARLINGS

• FAMILIARITY AND UNFAMILIARITY

• LISTENING TO THE ARCHIVES, LETTING THEM SPEAK FOR THEMSELVES

AW Joost Grootens was the department head of MA Information Design at Design Academy Eindhoven, one of his motto: Listen to the data!

1 HOW TO BEGIN?

• RECOGNISING AND RECKONING WITH THE NATURE OF ‘ARCHIVE’

“Archives, it seems, are everywhere, both in popular culture & academic discourse.”

Hal Foster, An Archival Impulse, 2004

AW There’s a fine line between being an archivist and a hoarder, and I could easily cross over into hoarding.

FD When I start my research I actually am a hoarder, gathering everything that even remotely piques my interest. Then after a while you know that a painful process of decluttering needs to start. I then go from hoarder to sorter to archivist.

“Any archive is a product of the social processes and systems of its time, and reflects the position and exclusions of different groups or individuals within those systems.”

Sue Breakell, Perspectives: Negotiating the Archive, 2008

“Focuault’s notion of the archive: whereas in the old archive individuals were used to build or substantiate categories, in the new archive categories are being used to build or substantiate the individual.”

Ernst van Alphen, When is Archiving Productive and When is it Not?, 2023

“Derrida also offers a psychoanalytic account of what attracts us to archives in the first place, regardless of their political and philosophical shortcomings. Because our Freudian death drive tends to erase the past, we rely on the archive as a form of prosthetic memory, toward which we run when we are overcome with ‘irrepressible desire to return to the origin, a homesickness, a nostalgia.‘ This self-defeating desire is what Derrida calls ‘archive fever‘.”

Tadhg Larabee, Archive Fever, 2022

“Functional archives are the infrastructure and control instruments that guide and support action in the present. Neither administration nor political power can do without them.” “Memory archives … only come into being when what is no longer of interest or relevance for the present or the future is sorted out but not immediately thrown away… a new consciousness arose for that which is past and from which no normative force emanates any more, but is still of interest: history.”

Aleida Assmann, The Archives as a laboratory of the New: Where Remembering and Forgetting Meet, 2023

“Digital archives are often seen as a democratised solution to the issues raised by the role of the host institution and its selection processes, and by the paradox of wanting to keep everything yet the impracticality of doing so… The internet suggests permanence by using terms such as ‘auto-archiving’, but this is an illusion. The material needs to be actively captured and preserved. Archives that survive must inevitably be kept in some kind of houses of memory, whether real or virtual.

A Sue Breakell, Perspectives: Negotiating the Archive, 2008

ST An online archive does not immediately equate to accessibility. It still have to be actively maintained by a caretaker. I have often found that the most fruitful searches result from conversations with archivists, whether online or in person.

AW The search process is definitely an artistic adventure. It takes patience and creativity, especially when we have to tweak keywords or categories and be open to unexpected results. Indeed, working with an archivist feels like a luxury—it makes the whole experience more insightful and rewarding.

FD It makes me think of the work of Deep listener and researcher Ximena Alarcón Díaz. You could say that the archivist themselves are the embodiment of the archive, containing all of the intangible context of the physical archive. And therefor indispensable to our artistic research as conversations with archivists will always unearth new material.

“Exclusions are inherent to any archival organisation. This explains why memories and knowledge ‘outside the archive’ are also part of the archive, in the sense produced by archival rules of exclusion.

Ernst van Alphen, When is Archiving Productive and When is it Not?, 2023

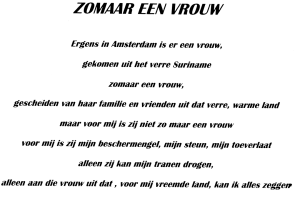

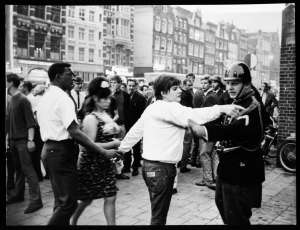

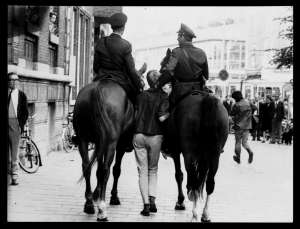

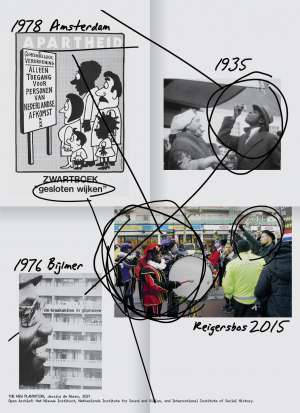

“… Immigrant bodies continue to be rendered into archival materials, reshaped and co-opted for political gain… Migrant bodies are continuously expected to reassure and attest to their origins and right to be here. One’s legal status, employment status, economic productivity, English fluency, religious affiliations, and loyalty to the host country are continuously performed to avoid the humiliation of non-belonging.

James Nguyen, Làm Chó Bó / Making Trouble, 2020

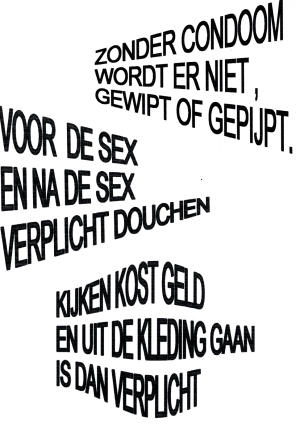

ST I think there is a specificity with immigrant radio programmes in which they become dedicated spaces for people whose voices are not heard and who are not often encouraged to speak. Immigrant radio is accessible by the mainstream but is not restricted by it.

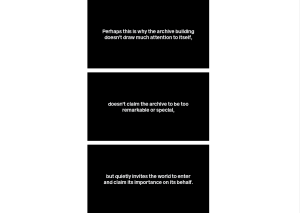

“An archive designates a territory – and not a particular narrative. The material connections contained are not already authored as someone’s – for example, a curator’s – interpretation, exhibition or property; it’s a discursive terrain. Interpretations are invited and not already determined.

Sue Breakell, Perspectives: Negotiating the Archive, 2008

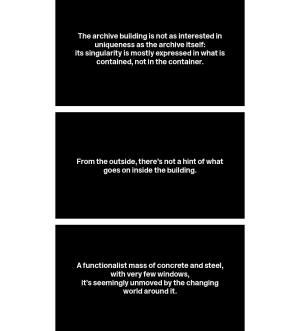

FD I find that every archive I’ve visited did exactly that: presenting a particular narrative. It would reveal itself in the choice of material that was archived, in the sort of objects that were archived, the way it was archived (chronological, alphabetical, completely random chaos…).

“If the archive cannot be a site for self-representation, it can under certain circumstances provide a space for contestability, activism, and perhaps even retribution. Therein lies the paradox of the archive.

James Nguyen, Làm Chó Bó / Making Trouble, 2020

• UNDERSTANDING RADIO AS A MEDIUM

“Invented only in 1895, radio made it possible to bypass print and summon into being an aural representation of the imagined community where the printed page scarcely penetrated.

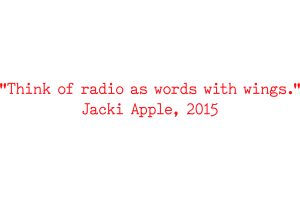

Benedict Anderson, Imagined Communities, 1983

“Radio affects most people intimately, person-to-person, offering a world of unspoken communication between writer-speaker and listener. That is the immediate aspect of radio. A private experience. The subliminal depths of radio are charged with the resonating echoes of tribal horns and antique drums. This is inherent in the very nature of this medium, with its power to turn the psyche and society into a single echo chamber.

AW This is what parasocial means, right?

FD And through those airwaves you can encounter what Franziska Schroeder calls ‘Networked Listening’, which provokes an “unselfing” or the “state of moving from oneself to the other.” It has the potential of becoming a conductor of compassion.

ST True. I am also fascinated by how intimacy and memory are created through the medium of radio. Closeness comes easily when we remember, from listening passively to recalling actively.

“Radio is provided with its cloak of invisibility … It comes to us ostensibly with person-to-person directness that is private and intimate … a subliminal echo chamber of magical power to touch remote and forgotten chords.

“Radio gives privacy, and at the same time it provides the tight tribal bond of the world of the common market, of song, and of resonance.

All Marshall Mcluhan, Understanding Media: The Extensions of Man, 1964

“Imagine radio that, instead of numbing us to sounds, strengthens our imagination and creativity instead of manipulating us into faster work and more purchasing, it inspires us to invent; instead of overloading us with irrelevant information and fatiguing us, it refreshes our acoustic sensitivity; instead of moving us to ignore thoughts and surroundings, it stimulates listening; instead of broadcasting the same things over and over again,it does not repeat; instead of silencing us, it encourages us to sing or to speak, to make radio ourselves; instead of merely broadcasting at us, we listen through it.”

Hildegard Westerkamp, The Soundscape in Radio, 1994

• WHAT/WHO TO LISTEN FOR?

“Most radio engages in relentless broadcasting, a unidirectional flow of information and energy, which contradicts the notion of ecology. What would happen if we could turn that around and make radio listen before imposing its voice like an alien into a new environment? What if radio was non-intrusive, a source for listeners and for listening? Can radio be such a place of acceptance, a listening presence, a place of listening? Is it possible to create radio that listens, that in turn encourages us to listen to, and hear, ourselves?”

Hildegard Westerkamp, The Soundscape in Radio, 1994

AW Answering these questions in a contemporary light - happy to see something is happening: IG@aview.fromabridge (A person on a bridge picks up a phone and shares their view with the world).

“Perhaps it is true that we do not really exist until there is someone there to see us existing, we cannot properly speak until there is someone who can understand what we are saying.“

Alain de Botton, Essays in Love, 1993

AW Radio may not be as effective as a standalone medium without the phone-in sessions or interaction between the hosts and their audience.

FD Going back to my teenage self though, even just the idea of there being more of “me” out there while tuning into a radio-show made me feel less alone.

“In radio, you have two tools. Sound and silence.“

Ira Glass

“We’re surrounded by signs; our imperative is to ignore none of them.“

Jonathan Lethem, Ecstasy of influences, 2007

“In some ways, making radio is like composing music. The same care for form and content has to be taken in creating radio as in creating a piece of music. The same questions arise: when to have sound and when to have silence; what sense of time to create what sounds to select; what to say and how to say it; how to retain the dimensions of silence under a stream of sound; how to attract and keep a listenership.”

Hildegard Westerkamp, The Soundscape in Radio, 1994

ST Silence is an interesting concept with live radio shows. The term “dead air“ is damning. However, I was listening to an interview with Brené Brown the other day and she took her time and paused frequently. The use of silence was informative and as a listener, I followed along.

FD Which is why I’m so attracted by independent radio where dead air is not a threat but a tool. Where sonic landscapes of voices, music, field recordings and other material is free to find its own radio rhythm.

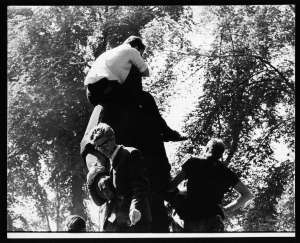

“They danced entranced to the tribal drum of radio that extended their central nervous system to create depth involvement for everybody.“

Marshall Mcluhan, Understanding Media: The Extensions of Man, 1964

“A politics of listening sits uneasily with any form of institutionalisation, whether as a party or not. Institutions tend to have rules or practices which define expectations and tune in to certain voices, but not others. Institutions are not very good at listening even when they try to do it”.

John Holloway, Crack Capitalis, 2010

“Sound and listening are situated as the basis for capacities by which to nurture an insurrectionary sensibility – a potential found in the quiver of the eardrum, the strains of a voice, the vibrations and echoes that spirit new formations of social solidarity – and that may support an engagement with the complexities of contemporary life.”

“The hearing that is the basis for an insurrectionary activity, a coming community.”

Brandon LaBelle, Sonic Agency: Sound and Emergent Forms of Resistance, 2018

2 HOW TO RESEARCH?

• WHAT ARE THE ROLES OF ARTIST-RESEARCHER-DESIGNER IN ARCHIVAL RESEARCH?

“Drifting from signifier to signifier, the artist invents meandering trajectories between cultural signs.“

Claire Bishop, Information Overload, 2023

ST I believe it was in one of Louise Glück’s poems that she wrote “We look at the world once, in childhood. The rest is memory.” Perception is a learnt behaviour. Artist-researcher-designer enters an archive to reinvent this behaviour.

“The work in question is archival since it not only draws on informal archives but produces them as well, and does so in a way that underscores the nature of all archival materials as found yet constructed, factual yet fictive, public yet private. Further, it often arranges these materials according to quasi-archival logic, a matrix of citation and juxtaposition, and presents them in a quasi-archival architecture, a complex of texts and objects.“

Hal Foster, An Archival Impulse, 2004

“Archivists find that researchers not only come with ideas of what they hope to find but also cannot accept that it is not there. There is an expectation of completeness. But, in reality just as much as in theory, the archive by its very nature is characterised by gaps.“

Sue Breakell, Perspectives: Negotiating the Archive, 2008

ST I personally are not too caught up with missing information. I think if I were to work as a journalist, I would become more obsessed with filling the gaps. Perhaps art does the opposite, it is obsessed with absence.

FD But that absence we try to fill right? We fill those liminal spaces with our own thoughts, ideas, concepts, words, sounds, works. Adding new archive material to the ever expanding archive.

“Failing to recognise that not all historical gaps can be brought into institutional and archival art, not all archival material should be up for grabs.“

James Nguyen, Làm Chó Bó / Making Trouble, 2020

“Lists are also a very simple manifestation of one’s desire to order and to control, while acknowledging all along two universal rules, that whenever possible, destiny will take the path of the least resistance, and that chaos is inherent in all that surrounds us.“

Fiona Tan, Mountains and Molehills, 2022

ST Serendipity. I am into that.

FD I love improvising with chaos.

“Inspiration could be called inhaling the memory of an act never experienced. Invention, it must be humbly admitted, does not consist in creating out of void but out of chaos. Any artist knows these truths, no matter how deeply he or she submerges that knowing.“

Jonathan Lethem, Ecstasy of influences, 2007

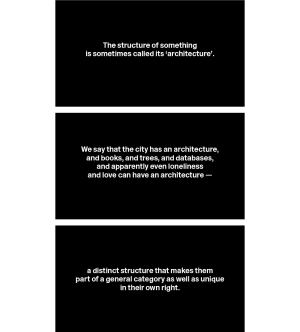

“But once one is inside an archival organisation, other problems arise: one does not exist in one’s unique, individual specificity but as an example of how one is categorised in the archive. “

Ernst van Alphen, When is Archiving Productive and When is it Not?, 2023

“I think the archive is a central component of the ambivalence that artists can feel towards making things at all, and situating them in the world at large, and within their own story of their life and work. At some point in their life artists usually confront, and answer in their own way, the following questions: ‘Why add anything more to the already overburdened culture?‘ And, ‘Why produce more stuff, which is going to become a commodity and lose all its original, critical meaning?‘“

Judy Vaknin, Karyn Stuckey, Victoria Lane (ed.), All This Stuff: Archiving the Artist, Artists and archives: A Correspondence (Between Uriel Orlow and Ruth Maclennan), 2013

ST I’ve heard and read from many artists that not-making was not an option. What do we think about the abundance (or overloading) of information?

FD Sometimes I wonder about the archiving of my radio practice. I would actually prefer the broadcasts to only exist in their own time and space. To exist only for the (small group) of listeners and myself.

• HOW DO WE PERCEIVE AND CONCEIVE INFORMATION FOUND IN AND ALONGSIDE AN ARCHIVE?

“Obviously [the internet] is always my first point of contact with a subject and many times it leads me to investigate things in a less methodological way, a richer way. It situates normal people, everyday people, at the same level as books and official sources. [The] internet is present all the time, and I don’t blame it for often being wrong. I like it. What better way to divert an investigation towards something contradictory or further from the truth. It is there that one finds relations that potentially become something interesting.“ Mario García Torres, The Structures of Art: An Interview with Mario Garcia-Torres, 2012

FD Finding other methodologies is at the core of what artistic research should be about for me. Why hold on to this predetermined notion of doing research set by the academic world?

ST Ditto. The shaping of research methods is a much longer trajectory than one project. The art that I am attracted to usually shows a great commitment to their methods. Academic research methods tend to be observational and descriptive, but could also become restrictive and didactic. The process is never as tidy as it sounds.

“Martin Heidegger held that the essence of modernity was found in a certain technological orientation he called “enframing.” This tendency encourages us to see the objects in our world only in terms of how they can serve us or be used by us.“

Jonathan Lethem, Ecstasy of influences, 2007

“Our task is to make trouble, to stir up potent response to devastating events, as well as to settle troubled waters and rebuild quiet places. Staying with the trouble requires making odd-kin; that is, we require each other in unexpected collaborations and combinations, in hot compost piles. Lots of trouble, lots of kin to be going on with.”

Donna Haraway, Staying with the Trouble: Making Kin in the Chthulucene, 2006

FD “Standby.

This is the time.

And this is the record of the time.

This is the time.

And this is the record of the time.

Put your hands over your eyes.

Jump out of the plane.

There is no pilot.

You are not alone.

Standby.

This is the time.

And this is the

record of the time.”

Laurie Anderson - From The Air, 1982

“The same archival burdens that blunts our capacity to fully access self-representation provides us with the motivation to confide in the family and collude in alternative strategies towards imperfect forms of self-determination. “

James Nguyen, Làm Chó Bó / Making Trouble, 2020

“Other fundamental principles underpinning archive theory and practice – authenticity and the context of the record – are also eminently compatible with postmodernist thought in demanding that we do not take a document at face value but rather look at the process of creation rather than the product itself.“

Sue Breakell, Perspectives: Negotiating the Archive, 2008

• IT’S ALWAYS PERSONAL: MEMORIES VS. UNDERSTANDING

“I understand archives as places where remembering and forgetting meet.“

Aleida Assmann, The Archives as a laboratory of the New: Where Remembering and Forgetting Meet, 2023

AW This is a poetic observation. I view the world through the lenses of familiarity and unfamiliarity, allowing me as a designer to navigate between these extremes. My goal is to transform what I may have overlooked into something I can see with fresh eyes, or to take something that feels alien and make it relatable.

ST I am staying with the poetics: a pendulum between learning and unlearning…

“Our memory limits what stories we see in the archive, and the archive limits what information is available to our memory.“

Tadhg Larabee, Archive Fever, Boston Review, November 17, 2022

“The act of remembering involves both storing and retrieving: it is not a passive process, especially in the digital age. To be able to confirm the original context and provenance of archives will become more important than ever.“

Sue Breakell, Perspectives: Negotiating the Archive, 2008

“Preventing forgetfulness, stopping the disappearance of things and beings seemed to me a noble goal, but I quickly realised that this ambition was bound to fail, for as soon as we try to preserve something, we fix it.“

Christian Boltanski

“In order to recognize an anachronism, one must know the difference between the present and a past era. This cannot be done without archives, which are the prerequisite for this invaluable cognitive achievement and the basis of historical education. Only this education makes it possible to expand one’s knowledge of one’s own past, to think critically beyond the narrowing of traditions handed down and a one-sided image of oneself, and thus also to recognise the foreign in one’s own.“

Aleida Assmann, The Archives as a laboratory of the New: Where Remembering and Forgetting Meet, 2023

3 HOW TO TRANSLATE?

• KILL YOUR DARLINGS

AW Haha! Simpson and I are getting pretty good at it. Like I said earlier, it’s easy to slip into hoarding, but our approach is to let things go so we can refine the content. Otherwise, if everything speaks at once, it’s just noise, it’s pollution!

ST I think it’s also about the quality of attention we are trying to cultivate. I am becoming less convinced by the passive quality of an installation and more drawn to event-based presentations.

FD I’m still practicing :). But I think that’s also why I love event based presentations like Simpson. For me they allow my love of improvisation to take the reign and let the moment refine the content.

“I didn’t have time to write a short letter, so I wrote a long one instead.“

Blaise Pascal, Lettres Provinciales, 1657

“Artists are surrounded by potential things that carry meanings which they may or may not put to use in a context that will endow them with many other meanings, through association, and make them art.“

Judy Vaknin, Karyn Stuckey, Victoria Lane (ed.), All This Stuff: Archiving the Artist, Artists and archives: A Correspondence (Between Uriel Orlow and Ruth Maclennan), 2013

“If you collect everything, you collect nothing.“

Fiona Tan

“What will the sheer volume of material mean for researchers in the future, especially if it is decontextualised and without external authentication… Keeping everything is not a solution.“

Sue Breakell, Perspectives: Negotiating the Archive, 2008

“Getting rid of the boring parts, and going right to the part that are like getting into your heart, you know you just have to be ruthless.“

Ira Glass, Ira Glass on Storytelling, 2013

FD My problem is I’m never bored.

“… research-based art prizes open a gap between research and truth: Rather than being grounded in social themes (migration, translation, female labor, environmental damage), the artwork pulls disparate strands together through fiction and subjective speculation… For fabulation to have critical currency, it matters which histories are being retrieved and why.“

Claire Bishop, Information Overload, 2023

• BETWEEN FAMILIARITY AND UNFAMILIARITY

“André Breton’s maxim ‘Beautiful as the chance encounter of a sewing machine and an umbrella on an operating table‘ is an expression of the belief that simply placing objects in an unexpected context reinvigorates their mysterious qualities.“

Jonathan Lethem, Ecstasy of influences, Harper’s Magazine, February, 2007

“How do you end a story that’s not yours? Add another sentence where there is a pause? Infiltrate the story with a comma when really there should have been a period? Punctuate with an exclamation point where a period would have sufficed? What if you kill something breathing and breathe life into something the author wanted to eliminate? How do you get inside the mind of a person who isn’t there? Fill the shoes of someone who will never again fill his own?”

Shaila Abdullah

“This is not a will to totalize so much as a will to relate—to probe a misplaced past, to collate its different signs (sometimes pragmatically, sometimes parodistically), to ascertain what might remain for the present… It assumes anomic fragmentation as a condition not only to represent but to work through, and proposes new orders of affective association, however partial and provisional, to this end, even as it also registers the difficulty, at times the absurdity, of doing so. This is why such work often appears tendentious, even preposterous.“

Hal Foster, An Archival Impulse, 2004

“Sound curation that starts from what sounds, from the invisible of sonic materiality, that which is neither seen through the expectations of visual arts nor via a musical language, is an experiment, an aesthetic Hadron Collider, that seeks to grant us access to another way things are but we cannot yet see. In this way curation becomes central in the intention to reach those dark particles, the dark matter of sound, to gain an understandings of the other, unperceived dimensions of the world which are not other worlds but slices of this world; and to comprehend their consequences - aesthetically, politically and scientifically.”

Salomé Voegelin, Listening as Strategy for Research for and from the Arts, 2021

“This recycling of sounds, images, and forms implies incessant navigation within the meanderings of cultural history, navigation which itself becomes the subject of artistic practice. Isn’t art, as Duchamp once said, “a game among all men of all eras?” Postproduction is the contemporary form of this game.“

Nicolas Bourriaud, Postproduction. Culture as Screenplay: How Art Reprograms the World, 2006

AW Seems like it!

ST Designers work more like stylists, artists work more like production managers and “everyone is a DJ!”

FD And if we all are DJ’s then we all can perform live and postproduction is no longer a form of the game :)

• LISTENING TO THE ARCHIVES, LETTING THEM SPEAK FOR THEMSELVES

“The ear is hyperesthetic compared to the neutral eye. The ear is intolerant, closed, and exclusive, whereas the eye is open, neutral, and associative.”

Marshall Mcluhan, Understanding Media: The Extensions of Man, 1964

AW-ST We think the opposite.:

FD Completely agree with you both: so adding two quotes by Pauline Oliveros

“Deep Listening is active.

What is heard is changed by listening and changes the listener I call this the ‘listening effect’ or how we process what we hear. Two modes of listening are available - focal and global. When both modes are utilized and balanced there is connection with all that there is. Focal listening garners detail from any sound and global listening brings expansion through the whole field of sound.”

“Listening is directing attention to what is heard, gathering meaning, interpreting and deciding on action.

We hear in order to listen.

We listen in order to interpret our world and experience meaning. Our world is a complex matrix of vibrating energy, matter and air just as we are made of vibrations. Vibration connects us with all beings and connects us to all things interdependently.

We open in order to listen to the world as a field of possibilities and we listen with narrowed attention for specific things of vital interest to us in the world.

We interpret what we hear according to the way we listen.

Through accessing many forms of listening we grow and change whether we listen to the sounds of our daily lives, the environment or music.”

Pauline Oliveros, Quantum Listening, 1999

ST While we live in a time where information are constantly and aggressively coming at us and are inducing stress and fear of missing out, I hope that, at least in the realm of art and artistic research, we could forge a gentler, less-demanding space. To lend an empathetic ear, for each other, so to speak.

“Quoting from a written document is one thing. Listening to the soft spoken reflections and getting the nuances, the ‘ah’s’ and ‘uh’s’, the pauses and the thoughtfulness that are unheard by the transcription software I used, is for me a more intimate and instinctive method to spend with my material.“

Femke Dekker, Open Field, 2023

AW Not just more intimate, it’s more genuine, honest, and authentic.

“… the power of the archival for artists lies in this tension between matter and meaning: does the stuff that I accumulate mean anything, and how much control can I, or do I want to, have over that meaning? The archival document is a seductive metaphor for an object/fragment/trace that is not yet (and may never be) an art object,or an art idea.“

Judy Vaknin, Karyn Stuckey, Victoria Lane (ed.), All This Stuff: Archiving the Artist, Artists and archives: A Correspondence (Between Uriel Orlow and Ruth Maclennan), 2013

“’Traditionally the artist’s archive told the art historian more about the art’, whereas ’now we see increasingly how an artist can use it to tell us more about the nature of the archive.’“

Penelope Curtis, From Out of the Shadow, All This Stuff: Archiving the Artist, Artists and archives: A Correspondence (Between Uriel Orlow and Ruth Maclennan), 2013

”By choosing to make time-based art and to work with audiovisual media, I am condemned, so it would seem, to the transitory… all media are faulty, and yet each has its own intrinsic beauty… But all are most definitely translations, none represent reality… And yet in my own work as an artist, it is the translations that I must make do with, that I therefore welcome and embrace.“

Fiona Tan, Fiona Tan: Mountains and Molehills, 2022

ST And getting back to the nature of radio… What if art could be more like radio, an omnipresence which is accessible, non-expensive and communal. Can we still trust art? Or, does art still warrant trust?

FD Was art ever meant to be trusted? For me art is meant to disrupt, to awe, to question, to hold, to discard, to laugh at or with, to mirror and to reflect upon. Anything but trusted.

“Humans think in stories, and we try to make sense of the world by telling stories.”

Yuval Noah Harari

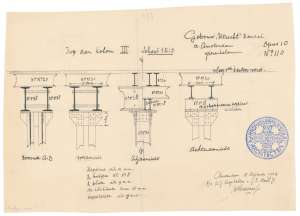

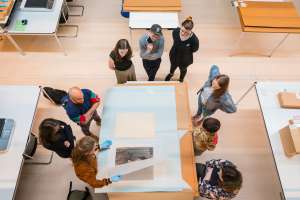

![(link: https://zoeken.hetnieuweinstituut.nl/nl/objecten/detail?q=trans&page=4&asset=16d043d5-c845-81af-e6dd-7be813be5251%3E text: Trans Europe Express [TEE] Modellen target: _blank), plaster model by Bout-van Blerkom, Elsebeth (architect), Werkspoor (opdrachtgever), Bout-van Blerkom, Elsebeth (maquettebouwer), 1953/1957. Objectnummer: MAQV591.03, Collectie Het Nieuwe Instituut.](https://www.openarchief.com/media/pages/blog/two-main-directions/206dd11d58-1563366616/e25db3aeb5daaaba2228f02ceedc6f4d94242a88f1ad8dc28ac39724d1559ce3-300x.jpg)

![(link: https://zoeken.hetnieuweinstituut.nl/nl/objecten/detail?q=trans&page=4&asset=16d043d5-c845-81af-e6dd-7be813be5251%3E text: Trans Europe Express [TEE] Modellen target: _blank), plaster model by Bout-van Blerkom, Elsebeth (architect), Werkspoor (opdrachtgever), Bout-van Blerkom, Elsebeth (maquettebouwer), 1953/1957. Objectnummer: MAQV591.03, Collectie Het Nieuwe Instituut.](https://www.openarchief.com/media/pages/blog/two-main-directions/206dd11d58-1563366616/e25db3aeb5daaaba2228f02ceedc6f4d94242a88f1ad8dc28ac39724d1559ce3-1800x.jpg)